Enabling collaboration in markets

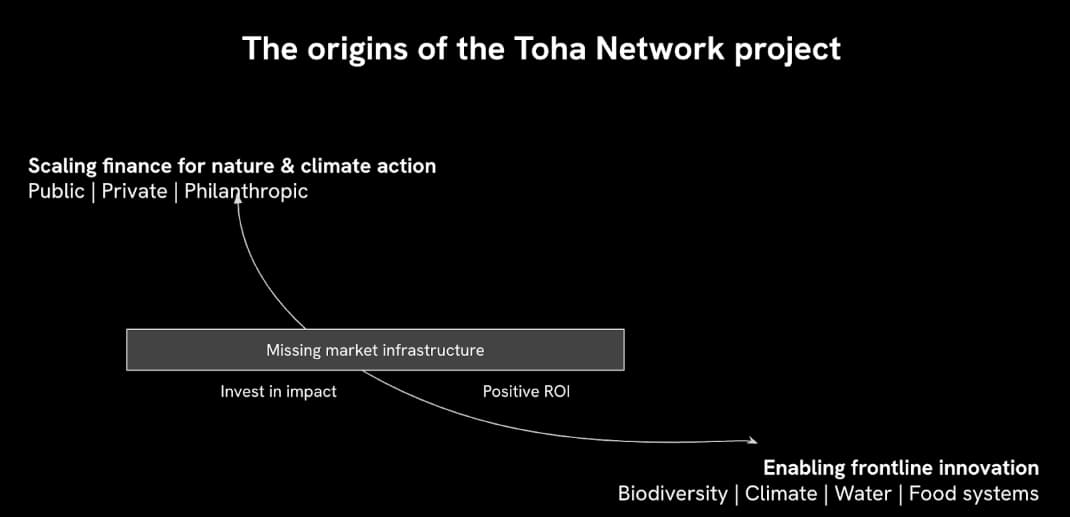

Let us begin with existing markets. On both the demand side and the supply side, the will to act on climate change and biodiversity loss is growing.

On the demand side, businesses have a range of motives to re-align their activities toward net-zero and nature-positive pathways. Some motivations are extrinsic – that is, compelled by forces from outside of the company. These include new environmental regulations, new expectations for financial risk disclosures, the pricing of emissions and other environmental externalities, and the need to maintain and expand market access. There are also intrinsic motivations which come from within the company itself. These include the heightened awareness that climate- and nature-related risks to business are material and intensifying, that company brands are vulnerable to misalignment with sustainability concerns, that employee recruitment and retention is improved by doing no harm, and that aligning with the future economy has competitive advantages. Various combinations of these motives underlie the growing commercial interest in investing in positive impact, which enables businesses to make associated claims about their sustainability attributes or credentials.

On the supply side, people have aspirations to do more to protect and restore the lands, forests, rivers and oceans that they live with and depend upon. Again, frontline communities have diverse motives which range from compliance with environmental regulation, to pragmatic interests in risk reduction, to duties of care and stewardship. However, frontline aspirations are rarely fully realised, commonly due to a shortage of funding and resourcing. For communities already on the economic periphery, this is doubly disadvantageous: the lack of access to finance hinders prosperity as well as self-determination.

One way to reduce the action gap is to join up the supply and demand for taking action on biodiversity and climate. This reduces the transaction costs of action, which are among the barriers to converting will into action. It also unlocks the capacity of self-organisation and coordination across greater scales.1 Well-designed markets are responsive to supply- and demand-side needs and preferences, which suits the distributed, dynamic and often highly localised nature of environmental challenges. It also mobilises businesses which have material interests in the global response to climate change and biodiversity loss, responsibilities to contribute, and ownership of many of the economic and technological means to do so. Thus, there is a positive case for markets, albeit markets that differ in design and purpose from those prevailing today.

As such, the market provision of environmental goods and services can complement – as opposed to substitute or crowd out – public sector and civil society initiatives.2 This coordination of market, state and social provision not only drives efficiencies, it is critical for a comprehensive response to ecological crises that sustains social support while reaching the necessary scale.

- Elinor Ostrom (1990). Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action. Cambridge University Press.

- Katie Kedward, Sophus zu Ermgassen, Josh Ryan-Collins and Sven Wunder (2023). Heavy reliance on private finance alone will not deliver conservation goals. Nature Ecology and Evolution 7, 1339–1342.