The missing market infrastructure

To match supply and demand, there is a need for new systems of collaboration. The Toha system meets this need with digital public infrastructure that is designed to reveal the value of impact through time.3 This ‘missing market infrastructure’ has three pillars:

- A measurement platform which uses impact data technologies to track actions and outcomes.

- A data sharing network for the secure and sovereign exchange of impact data.

- A payment system for the secure and sovereign exchange of impact data.

These pillars create an integrated, high-integrity system that bridges the gap between supply and demand for action on climate and nature. Further, they create the conditions of trust which underpin the system’s self-sufficiency, legitimacy and durability. This infrastructure is being built by the Toha Network, an ecosystem of ventures, impact investors, scientists and communities who are laying the foundations for radical collaboration.

Measurement platform

Measurement establishes a relationship with physical reality. It produces data, which is a representation of real things, such as trends in ecosystems and populations, and measurable outcomes of human action. This data can support better local management, but also enables effective relationships at a distance; for example, funders and investors who wish to produce positive impact in other regions, or asset managers who wish to prudently manage resources in remote locations.

Data also enables organisations and individuals to make robust claims. Claims can be defined as assertions that describe, distinguish or promote a product, process, business, service or action with respect to its social, environmental or financial attributes or credentials. Thus, in respect to nature and climate change, an organisation might make:

-

a reporting claim – that is, a claim of climate- or nature-aligned attributes which already exist within a company’s value chain.

- e.g. Company X has located and identified 1,000 hectares of regenerating native forest on the farm properties of its suppliers.

- e.g. Company X has not applied synthetic nitrogen fertiliser in its land management practices for 5 years, which is associated with the avoidance of freshwater degradation and species loss.

-

a contribution claim – that is, a claim of contribution to a local or global target by causing impact beyond the company’s own value chain.

- e.g. Company X has contributed to Country Y’s emissions reduction target by investing in technologies that avoided 100,000 tonnes of carbon dioxide emissions.

- e.g. Company X has contributed to Country Z’s alignment with Target 2 of the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework by funding the restoration of a degraded forest ecosystem.

-

a compensation claim – that is, a claim that an unabated harm within a company’s value chain is compensated for by investing in an inversely equivalent impact.4

- e.g. Company X has compensated for 10,000 tonnes of carbon dioxide emissions by voluntarily purchasing 10,000 removal units from a carbon mineralisation project.

- e.g. Company X has compensated for the biogenic methane released by ruminant livestock by converting several land blocks into native forest, thereby neutralising the climate forcing impact of a short-lived greenhouse gas with temporary carbon storage.

In the Toha system, these claims are formalised as claim templates. These are reproducible, science-based digital templates which guide the user through the measuring, monitoring, reporting and verification (MRV) of actions and outcomes. This produces a data asset that can be accessed by organisations for the purpose of making verifiable claims, such as those discussed above. The proceeds of sales from data access rights can then be allocated to those who created the data – that is, the frontline communities who are taking action and reporting its impact.

The Toha system also facilitates pledges. These are a type of commitment claim – that is, an ex ante claim that a target or desired state will be achieved in time. The Toha pledge is made by the suppliers of future impact: it is a commitment to specific activities and milestones, as well as to collect and report on relevant data. Pledges are formalised as pledge templates which specify the activities to complete and the data to report. Pledges are a digital contract which can facilitate the upfront financing of activities and data collection, and therefore enable investors to make robust claims on subsequent actions and outcomes.

To realise and sustain value, Toha’s impact data technologies (i.e. claim and pledge templates) must be high integrity and aligned with supply- and demand-side needs. Consequently, claim and pledge templates are developed by subject matter experts in a marketplace created by Toha. Template developers receive royalties for the use of their templates over time, which creates the incentives for ongoing refinement and innovation. Further, the template development process is shaped by supply and demand – that is, the needs of investors, the aspirations of frontline communities, and the entrepreneurialism of template developers who see an opportunity to create public value by operationalising specialist knowledge, whether conventional Western science, Indigenous knowledge, or innovative measurement approaches. Toha will not predetermine the pipeline of claim templates for development, but does facilitate quality assurance and quality control by rigorous processes of peer review.

Data sharing network

Data can be precious. It is precious when the things that data represents are precious. People, animals, forests, grasslands, mountains, rivers, oceans and skies are precious. Nature – which encompasses all of this and more – is precious. Consequently, the data that represents nature carries its preciousness with it.

This is why data sovereignty is central to the Toha system. Recent advances in digital technology make data more open and accessible than ever, which creates new opportunities to derive and extend value from data. Its value proliferates through use and reuse – by being shared, analysed, converted, interpreted, and incorporated into decision making. However, there are risks associated with open data. This includes longstanding concerns about the right to privacy and freedom from discrimination, but also more novel challenges such as the appropriation and exploitation of data by intermediaries or third parties. If such risks eventuate, if data is misused or mishandled, this can cause harms that flow through to the things being represented – to people and the nature they are part of. Potentially, this could trigger a backlash against the openness of data which undermines its capacity to generate public value.

To have data sovereignty is to have the power to ensure that data with which one has a special relationship is used only in ways that one consented to. This is a power that can be held by persons or peoples, and relates to data which represents them, their belongings, their lands and surroundings, their cultures and traditions, their relationships to others and to nature. Data sovereignty is linked to universal rights of autonomy and dignity, and self-determination for all peoples. However, its relevance is heightened for Indigenous peoples whose unique connections to places and species are endangered by past and present processes of colonisation; and for farmers, landowners and local communities who carry outsized risks in the global food system. For this reason, the Toha system positions data sovereignty as the minimum operational requirement for a market-based economy that recognises and rewards the stewardship of nature.5

To operationalise this commitment, Toha ensures that ownership of nature-related data remains with data providers. What is transacted through the data sharing network is not data assets, rather the right to access data. This means that data providers remain exposed to the future benefits that accrue as data is used and reused over time. It also enables data providers to give or withhold consent over how data is used and for what purpose, and thereby to exercise influence in the data economy.

By generating powers and rights, data sovereignty empowers the providers of data to share in its benefits. In this vein, others have argued for valuing data as if it were a form of labour.6 Whether it is the data we produce deliberately by measurement and reporting, or the data we produce inadvertently when we interact with online platforms, this data-as-labour is the engine of the digital economy. By declaring such data as labour, we claim ownership over the data and its value.

Presently, data-as-labour is rarely fairly valued. When data is required for regulatory or disclosure purposes, the burdens of measurement and reporting are typically pushed downstream to those with the least resources to do this; for example, small businesses or landholders at the end of supply chains who must provide scope 3 data to global food brands. Similarly, when the commercial value of big data is appropriated by very large online platforms, the benefits are not always shared fairly with the people who created that data by interacting with the platform. This is what happens when sovereign power is highly centralised in the data economy.

By contrast, when data sovereignty is decentralised, ordinary people are empowered to choose whether the value of data is freely given, or whether benefit sharing is required. For those in work in service to nature, the recognition of data-as-labour can unlock much-needed contributions to funding and resourcing – that is, a positive return on the investment of time into making, measuring and reporting impact. This deepens the reciprocity of the data economy, such that the value created by data is returned to the people who produced it, which in turn enables further frontline impact and associated data collection.7 When data that represents regenerative impact is valuable, the data economy enters into positive feedback with the regenerative economy, a cycle of mutual reinforcement.

Impact payment system

The final pillar is an impact payment system to facilitate the funding and financing of impact. This is an important practical component of the Toha system: firstly to facilitate grants, debt and equity for impact; and secondly to establish a data economy that enables the value of data to be realised and shared fairly among relevant participants.

It is critical that this impact payment system creates confidence among investors and purchasers of outcomes, both in terms of the security of the system itself, and verification that payments are generating the impacts they were intended to. It is equally critical that those supplying frontline labour and access to intellectual property also have confidence, especially in respect to the value with which they can transact. Arguably, time is more scarce than money when it comes to the urgency of climate action and nature regeneration – that is, we already possess most of the capacity and capability we need globally to address these challenges, but lack the time to mobilise and implement. Consequently, a key feature of Toha’s payment system is its recognition that one’s time has equal value to money when taking action and initiating impacts. Operationally, this means that a payment transaction in the Toha system can be initiated either by a trusted contribution of time in work, or by money.

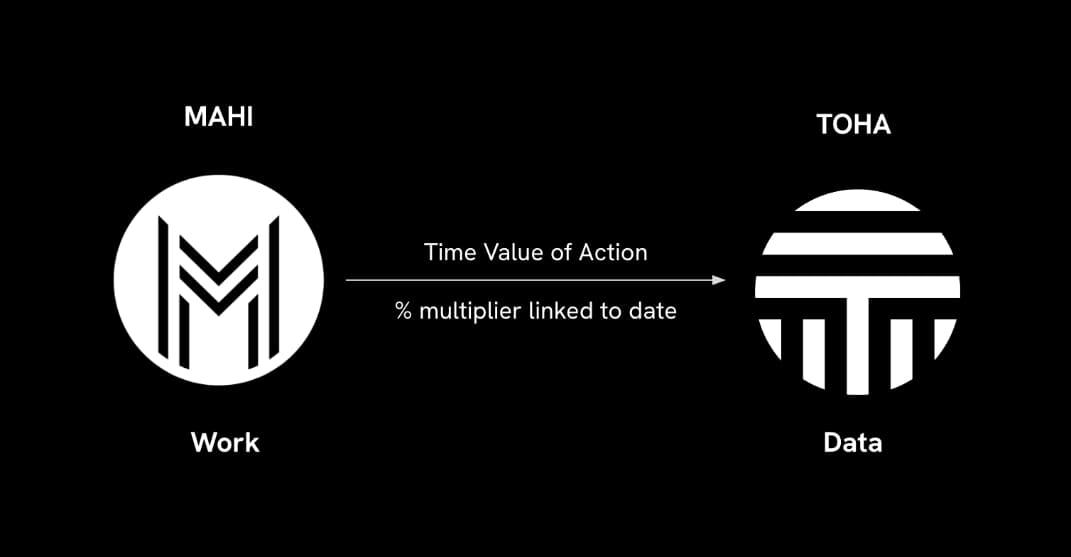

Digital token technology underpins Toha’s impact payment system to enable the integrated exchange of data and value. In its initial phase, Toha is using a dual-token system of MAHI and TOHA.

The word mahi in te reo Māori, the Indigenous language of Aotearoa New Zealand, refers to work, labour, performance and accomplishment. The word toha refers to distribution, allocation, and spreading around. By bringing MAHI and TOHA together in a token economy, Toha is designing for a more balanced distributive model between the providers of capital and the providers of labour.

The MAHI token represents a unit of funded work in service to nature and climate. By purchasing units, the buyers of MAHI are securely releasing funds for verifiable frontline action – that is, the actual work of repairing and restoring nature, and responding to climate change. In the initial phase of platform development, a lesser allocation of sale proceeds will also fund the design of impact data technologies to serve the Toha system.

The TOHA token generates rights to data and governance in the Toha system. Holders use TOHA to pay the transaction fees to access, use and share the data that is necessary for the operation of the impact payment system; or to purchase governance rights to influence the future direction of measurement efforts and the focus of the infrastructure. The tokenisation of active market membership will eventually enable future collective governance of the Toha system as a decentralised autonomous organisation (DAO). In the meantime, Toha has launched an open consultation to elicit market feedback on matters of network governance. The Toha system is intended to balance the incentives for those that fund the work via MAHI with the rewards for those who undertake the action. It will take active participation by all sides of the market to ensure that a credible regenerative pathway is followed.

A potential interaction in this dual-token system is the capacity to exchange MAHI for TOHA tokens. In the initial phase of the Toha system, in order to acquire TOHA, one must convert MAHI that they already hold by funding frontline action, contributing time to action, or contributing intellectual property. This is akin to a currency swap where MAHI, which represents proof of funded work, is exchanged for TOHA, which represents the right to access data to make claims of impact.

Through the design of this exchange, the Toha system has in-built incentives for early action that reflects the urgency of the climate and biodiversity crises. Essentially, a multiplier will be applied to MAHI upon its conversion to TOHA, but this multiplier is discounted over time in the lead-up to a target date. This mechanism is called the Time Value of Action (TVA). Its value within the Toha system is recorded in a unit of account, which is issued as a voucher at the rate of work verified by Toha against approved pledges. Thus, the earlier that action is taken and MAHI is earned, the greater the potential value of TOHA it can be swapped for. This enables the Toha system to reward the risks taken by early movers, and to increase their exposure to potential value uplift in the system. TVA is subject to changes and will depend on a separate agreement between the holders and the issuer. The first token allocations will target climate and nature targets for 2030. Further details on tokens are available in the Toha Network Terms of Service.8

As the marketplace matures, Toha envisions that networks of participants will manage these transactions on a distributed ledger, agreeing to minimum standards and market rules for the facilitation of potential MAHI–TOHA swaps. The aim is to operationalise reciprocity in an escalating exchange of shared responsibility, with trust and reputation earned and sustained in community marketplaces.

See the for more information about the tokens generally.

- Digital public infrastructure is defined as: ‘A set of shared digital systems which are secure and interoperable, built on open standards, and specifications to deliver and provide equitable access to public and/ or private services at societal scale and are governed by enabling rules to drive development, inclusion, innovation, trust, and competition and respect human rights and fundamental freedoms.’ India’s G20 Presidency and UNDP (2023). Accelerating The SDGs Through Digital Public Infrastructure: A Compendium of The Potential of Digital Public Infrastructure.

- The role of compensation claims in net-zero, nature-positive pathways is under growing scrutiny. This is warranted and necessary. For instance, the like-for-like treatment of forestry carbon removals and carbon dioxide emissions in conventional carbon markets is not supported by existing science, because short-lived carbon storage in forests is not equivalent to long-lived storage in the atmosphere. To sustain trust and integrity, the Toha system, like any marketplace, must adopt rules to ensure that the market’s activities are consistent with its objectives. Eventually, this rule-setting will be delegated to collective governance. In the meantime, Toha will defer to international guidance and science. Hence, the examples of compensation claims given above are chosen to be scientifically defensible: long-lived emissions (CO2) with permanent removals (carbon mineralisation), and short-lived emissions (biogenic methane) with temporary removals (forest). Such designations may change in light of new science.

- Stephanie Carroll, Ibrahim Garba, Oscar Figueroa-Rodríguez, Jarita Holbrook, Raymond Lovett, Simeon Materechera, Mark Parsons, Kay Raseroka, Desi Rodriguez-Lonebear, Robyn Rowe, Rodrigo Sara, Jennifer Walker, Jane Anderson and Maui Hudson (2020). The CARE principles for indigenous data governance. Data Science Journal 19, 1-12.

- Eric Posner and Glen Weyl (2018). Radical Markets: Uprooting Capitalism and Democracy for a Just Society. Princeton University Press.

- John Reid, Matthew Rout, Jay Whitehead and Te Puoho Katene (2021). Tauutuutu: White Paper: Executive Summary. Report for Our Land and Water, National Science Challenges.

- Toha Network Terms of Service are available here: https://toha-network-trust.gitbook.io/toha-network-public-information/network-terms-of-service.